When my dad died last year, the head of his senior living facility asked, “What was it like to grow up with your father?” She had experienced firsthand his take-no- prisoner’s style. Dad was a tough man, endearing only to his children and grandchildren. My mother, who had waited on him hand and foot for 60 years, would never have called him endearing.

When my dad died last year, the head of his senior living facility asked, “What was it like to grow up with your father?” She had experienced firsthand his take-no- prisoner’s style. Dad was a tough man, endearing only to his children and grandchildren. My mother, who had waited on him hand and foot for 60 years, would never have called him endearing.

With my mother’s passing, I became his gal Friday: cook, cleaner, driver, financial planner and gardener. Oh yes, almost forgot, companion as well. The only problem was that I lived ninety minutes away. I still jump when the phone rings, wondering if it’s Dad with his usual inquiry. “Where are you?” A gravelly voice on the other end demands, “I need you now!”

After hanging up, I would rush down the interstate to clean up the flooded basement or to fill out financial forms. When my duties were fulfilled, his voice would soften and say, “Thank you, Sweetheart.” I don’t seem to recall him ever thanking my mother for all she had done. Somehow, he had found a bit of tenderness in his late eighties.

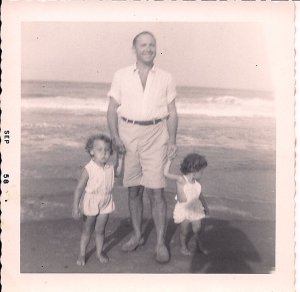

While we were growing up, Dad was all about caring for his family; self-employed with innumerable pressures, he wanted to give us the best opportunities. Yet, if we made so much as a peep to interrupt a conversation with my mother, there’d be a verbal lashing. Talking back was a capital offense in our house.

Dad, like so many of the depression era generation, scrimped on little luxuries (you didn’t dare order a coke when out to dinner), but, instead, saved for the big ones that really mattered: private school, college, summer camp and family vacations. Finally finding a gentler stride as a grandparent, Dad confessed that he thought he was a better grandfather than father. I would tell him now that he excelled at both.

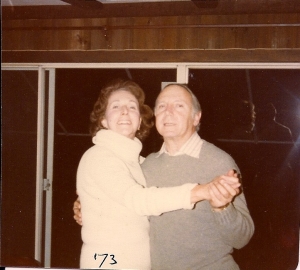

His body was as unbending as his spirit. Dad had never taken any medication, other than aspirin. Just two months before his passing, he had received high marks at his checkup. Yet, it was heart failure, or in my non-medical terms, broken heart syndrome that took his life. If it hadn’t been for a last minute pacemaker, Dad would have died peacefully in his sleep without ever having to enter a hospital. The little $62,000 machine, sewn into his 89-year-old chest, kept him alive for one debilitating month. That state-of-the-art device was no match for the hole my mother had left in his heart.

Two years and four months prior, my mother had died of cancer. She was dad’s lifeline to the outside world. She filled the house with good food, fresh flowers and laughing friends. We were surprised that he had lived as long as he did without her.

I performed my tasks during those caretaking years: nursing both my parents, selling a two-hundred-year-old house (not an easy job in this real estate market), finding an independent senior living facility up to his standards. It was exhausting, frustrating and often unbearable to be a parent to one’s parent. Knowing that time would eventually come, I still wasn’t prepared for such pressures.

My perspective was skewed, viewing my responsibilities as a burden, not a joy. As much as my husband and sister urged me, I struggled to enjoy dad’s company, too consumed by his everyday demands. Then, after all the months and years of being there for dad, I was absent physically and emotionally when it meant the most.

The week before dad died, an outbreak of super flu had caused his rehab facility to be quarantined. It was then that he had decided to die, only I didn’t know it (or I chose not to acknowledge it). The doctor and social worker had called to tell me to stay away for my own safety. According to them, he was doing fine and would be released by the end of the week. I was relieved that for once he wasn’t telephoning me. My sister was planning to fly in from Chicago to help with the move back to his senior living apartment.

On Wednesday, I kissed my dad, leaving him sitting up in a chair reading the New York Times. On Saturday, my sister and I found him lying in bed, unable to speak. When I first walked into the room, Dad’s eyes opened wide, as if to say, Where have you been? I hadn’t been there to help, console or comfort, when he needed me the most. No one had bothered to notice or alert us.

Soon after, Dad entered the final stage of dying. He was barely conscious, not able to open his eyes or speak. Did he know that he wasn’t alone? Now, there was suddenly so much to say. Words tumbled out, as I reassured him that he’d been a wonderful father and role model. Could he hear? More than anything I wanted a do-over of the past week, the past month,the past year. After the thousands of conversations about bank accounts, current events and politics, I never had the chance for the last one. The conversation that really mattered.